Bridging the Divide: Addressing Barriers to Cross-Institutional Collaboration Through the TRAVE Framework

Collaboration between community colleges and universities is not just beneficial—it is essential. These partnerships create seamless educational pathways, foster innovation in teaching and learning, and reduce persistent access obstacles. Despite their promise, meaningful collaboration between faculty and staff across these institutional types remains elusive. The barriers are rooted in structural, cultural, and interpersonal dynamics. This article explores the barriers to such collaboration and introduces the Transparency, Relevancy, Authenticity, Vulnerability, Equity (TRAVE) framework as a solution, grounded in the successful implementation of a cross-institutional summer bridge program design.

The Need: Why Cross-Institutional Collaboration Matters

Community colleges serve as a critical entry point to higher education. Nearly 40 percent of all postsecondary students begin their academic journey at a community college (Community College Research Center, n.d.), drawn by their accessibility, affordability, and commitment to teaching. However, despite these strengths, community colleges have faced prolonged criticism for their students’ low transfer and bachelor’s degree completion rates (Arum & Roksa, 2011; Beach, 2010; Brint & Karabel, 1989; Clark, 1960; Doyle, 2009; Weissman, 2024). Over the past decade, community colleges have developed a range of policies to address these issues. Jabbar et al. (2022) argue that successful transfer depends on more than academic preparation; it requires the accumulation of “transfer student capital”—the knowledge, confidence, and relationships that help students navigate institutional structures, understand transfer policies, and envision themselves as university students.

Summer bridge programs are promising interventions that build this capital. Traditionally designed to support incoming first-year students, these programs offer early exposure to college-level expectations, foster academic and social integration, and provide mentorship that can demystify the college experience. Increasingly, institutions are adapting summer bridge models to support transfer students, recognizing their potential to ease transitions and build momentum toward degree completion (McCord Ellestad et al., 2023; Rodriguez & Jacobo, 2021; Zuckerman et al., 2022).

While summer bridge programs are often framed as student-centered interventions, their potential to transform institutional relationships is equally powerful. Cross-institutional summer bridge initiatives create rare, valuable, and authentic opportunities for faculty and staff from community colleges and universities to work side by side, codesigning curriculum, sharing leadership, and aligning pedagogical goals. These programs also serve as incubators for institutional change.

The Emergence of TRAVE

For over five years, our team has run various cross-institutional summer bridge initiatives. Initially launched as an online engineering summer bridge camp for under-resourced high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic, the STEMTank program was designed to address both the digital divide and the lack of access to high-quality STEM experiences for students from rural and under-resourced areas (Traum et al., 2022). The team included university professors, community college faculty and staff, industry professionals, four-year university near-peer mentors, and incoming community college students (see Figure 1). As they worked in teams to solve authentic engineering problems, participants engaged in collaborative problem-solving and developed both technical and soft skills. The program culminated in participant presentations of their engineering solutions to a panel of “sharks”—a nod to entrepreneurial pitch competitions.

Figure 1: TRAVE Framework

The success of STEMTank led us to develop similar experiences in multiple cross-institutional contexts (Traum et al., 2022, 2024), including partnerships involving combinations of high school, community college, and university students. We have provided these summer bridge experiences in the form of one- or two-day workshops as well as semester-length adaptations. In all cases, we centered cross-institutional collaboration, breaking down the siloes that separate four-year universities, community colleges, and high schools. Cross-institutional teams co-developed the curriculum, co-facilitated sessions, and shared leadership responsibilities. Projects challenged students to undertake a novel engineering design to solve a problem. Essential to the design, faculty, mentors, and facilitators did not have a solution for the problem in mind, but rather, engaged with students in authentic discovery through trial and error. This process leveled the playing field, removing hierarchical barriers and modeling iteration based on experimentation as a natural component of the learning process.

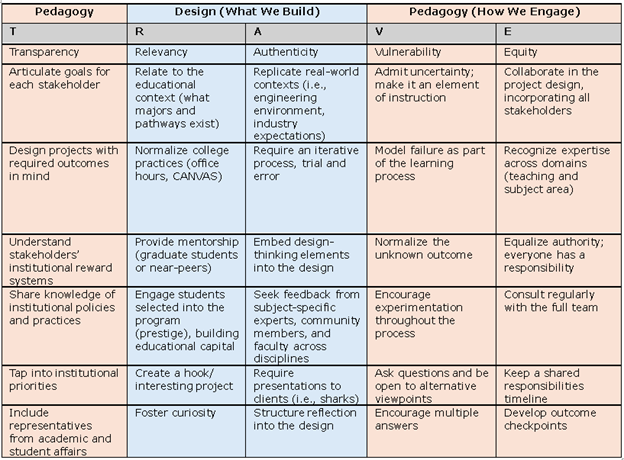

While we knew that cross-institutional collaboration was key to the success of these programs, we had not systematically analyzed the primary features of these collaborations. The TRAVE framework (see Table 1), a cross-institutional project design template, emerged from our teams’ efforts to identify the specific design elements that each project had in common.

TRAVE Framework

We began codifying the TRAVE framework in a series of meetings and interviews in spring 2025. During the first phase, each team member independently recorded elements of their programs that they considered crucial to their project’s success. We then divided each phase of the project's implementation, noting the responsibilities and shared construction of programming. Additionally, we conducted hour-long interviews with staff and faculty. In the final phase, we collaboratively coded individual lists and interviews using a thematic analysis approach. In team meetings, we also drew on literature to understand how these characteristics relate to pedagogical strategies.

Table 1: Design Elements and Pedagogical Approaches

Through this process, we developed the TRAVE framework based on five core principles: transparency, relevancy, authenticity, vulnerability, and equity. As indicated in Table 1, the framework considers both design elements (what we build) and pedagogical approaches (how we engage), and lays a foundation for authentic cross-institutional design, applicable to various summer bridge contexts and audiences. The following outline provides a working snapshot of the key elements of the TRAVE design.

Transparency

- Clearly articulate goals and expected outcomes for each stakeholder to ensure that all participants, whether from community colleges, high schools, or universities, understand their roles and contributions.

- Design the summer bridge programs with the outcomes in mind. Clarify how these elements relate to institutional reward systems and institutional policies.

- Develop a communication plan and assign responsibilities to all team members. Include milestones to measure incremental progress toward each stakeholder’s goals.

- Establish check-in periods to assess progress and make programmatic changes as needed.

Relevancy

- Ground projects in educational contexts relevant across institutions, aligning pathways for students to relevant majors and careers.

- Include team members from academic and student affairs to ensure holistic program design.

- Design project elements that normalize college practices, such as requiring students to utilize office hours and preexisting institutional resources.

- Include mentorship as a design component. Consider tapping into established networks, such as those of near-peer or graduate student organizations.

Authenticity

- Make real-world connections, such as design challenges that mirror professional scenarios.

- Allow for programmatic iterations. Be responsive to stakeholder input and seek clarification when necessary.

- Seek feedback from subject-matter experts and consider including community and industry advisors in the planning and reporting process.

Vulnerability

- Encourage experimentation and flexibility in project designs.

- Model failure as part of the learning process.

- Normalize unknown outcomes as a strategic outcome of the teaching and learning process.

Equity

- Recognize diverse forms of expertise, whether in teaching, subject matter, or student support.

- Design program components with shared authority in mind.

- Equalize authority between institutions and individuals, providing opportunities for all stakeholders to give feedback and request revisions to program designs.

Results and Impact

TRAVE framework implementation through summer bridge programs yielded significant and multifaceted outcomes for students, faculty, and staff. These outcomes extended beyond academic performance, influencing confidence, creativity, professional growth, and institutional relationships.

For students, TRAVE’s scaffolded interventions offered a transformative experience that combined hands-on challenges with mentorship and real-world applications. Participants reported increased confidence in their problem-solving abilities and a greater willingness to take intellectual risks (Traum et al., 2022). The framework’s emphasis on failure as a learning tool, central to TRAVE, helped students view setbacks as opportunities for growth. One student, for example, during a rocket-themed summer bridge, embraced a bold, creative design that ultimately failed to launch. Rather than being discouraged, she used the experience to deepen her understanding of engineering principles and to serve as a model of resilience for her peers. This shift in mindset, from fear of failure to curiosity and experimentation, was a hallmark of the program’s success.

Students also benefited from meaningful mentor relationships with college students and faculty. These relationships are encouraged to extend beyond the program's duration, with some students continuing to seek guidance from faculty and mentors months and years after the program concluded. The presence of mentors who were close in age and experience helped demystify the college journey and provided tangible examples of success. As one facilitator noted, the conversations between participants and mentors often had to be cut short, not due to lack of interest, but because they were so engaging that they could have continued indefinitely.

Faculty participants experienced a parallel transformation. For many, the program challenged long-held assumptions about failure, creativity, and instructional design. Prior to the intervention, some educators admitted to avoiding activities with uncertain outcomes, fearing that failure would demoralize students. Through their involvement and exposure to the bridge programs, these educators began to see failure not as a threat but as a necessary and productive part of the learning process. One member described how the experience gave her the confidence to try new instructional strategies and to trust that students would rise to the challenge, even when the path forward was unclear. This observation extends to high school participants. The researcher incubator hypothesis has been demonstrated in the past as a successful instructional management strategy for encouraging college students to embrace and take ownership of projects with unknown outcomes (Traum, 2009).

Faculty also reported that the program helped them reimagine their role in the classroom. Rather than being the sole source of knowledge, they became facilitators of inquiry, modeling how to navigate uncertainty and solve problems collaboratively. This shift was particularly impactful for educators working outside their area of subject expertise. One facilitator, with no background in engineering, described how the program helped her embrace vulnerability and develop a newfound interest in STEM. She credited the supportive partnership with cross-institutional faculty, especially the modeling of uncertainty and openness to failure, as key to her growth.

For staff, particularly those in student support roles, these bridge programs offered a rare opportunity to engage deeply with both students and faculty in a collaborative, interdisciplinary environment. Staff members noted that the program helped break down institutional hierarchies and fostered a sense of shared purpose. The relationships built during the workshops extended beyond the program itself, creating new channels for communication and collaboration between community colleges, high schools, and universities.

One staff member reflected on how the program changed her perception of students’ capabilities. Initially hesitant to push students too far, she was surprised and inspired by their resilience and creativity. This realization prompted her to rethink how she supports students in other contexts, emphasizing the importance of setting high expectations and providing the scaffolding needed to meet them. Watching college students mentor high school participants provided her with new insights into how to structure peer support and foster leadership among older students.

The impact of these programs was not limited to individual growth. Institutionally, the program fostered greater alignment between community colleges and universities. Faculty and staff from both sectors reported feeling more connected and more invested in shared goals. The collaborative design of each program, rooted in the TRAVE framework, helped establish a culture of mutual respect in which each partner’s expertise was recognized and valued. This cultural shift laid the groundwork for future collaborations and demonstrated the power of intentional, equity-focused partnership.

Lessons Learned

Implementing cross-institutional summer bridge programs comes with challenges. It requires time, trust, and a willingness to confront uncomfortable truths about institutional privilege and exclusion. However, the results were compelling. Faculty reported increased satisfaction with the collaboration process, students demonstrated greater confidence and persistence, and institutions began to align more closely on shared goals. Perhaps most importantly, the elements described in TRAVE created a culture of mutual respect and curiosity that continues to shape our work.

Next Steps

TRAVE is not a fixed model but a living framework that can be adapted and expanded to meet the diverse needs of various institutions and communities. Our next steps include conducting formal evaluations of TRAVE’s impact, developing training modules for faculty and staff, and creating a digital toolkit to support implementation. We also plan to scale the framework by partnering with additional colleges, universities, and international partners.

In a time when higher education faces unprecedented challenges, the need for authentic, equitable partnerships has never been greater. The TRAVE framework provides a template for collaboration, grounded in transparency, relevance, authenticity, vulnerability, and equity.

References

Arum, R., & Roksa, J. (2011). Academically adrift: Limited learning on college campuses (1st ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Beach, J. M. (2010). Gateway to opportunity? A history of the community college in the United States (1st ed.). Stylus Pub.

Brint, S., & Karabel, J. (1989). The diverted dream: Community colleges and the promise of educational opportunity in America, 1900-1985. Oxford University Press.

Clark, B. R. (1960). The open door college: A case study. McGraw-Hill.

Community College Research Center. (n.d.). Community college FAQs. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/community-college-faqs.html

Doyle, W. R. (2009). The effect of community college enrollment on bachelor’s degree completion. Economics of Education Review, 28(2), 199-206.

McCord Ellestad, R., Keffer, D. J., Retherford, J., & Kocak, M. (2023, June 25-28). Outcomes & observations in the transfer success co-design in engineering disciplines (TranSCEnD) program at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Conference, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Jabbar, H., Schudde, L., Garza, M., & McKinnon-Crowley, S. (2022). Bridges or barriers? How interactions between individuals and institutions condition community college transfer. The Journal of Higher Education, 93(3), 375-398.

Rodriguez, C. A., & Jacobo, C. (2021, May 10). Educational Opportunity Program, transfer bridge: A transfer student transition program. The Latest. https://naspa.org/blog/educational-opportunity-program-transfer-bridge-a-transfer-student-transition-program

Traum, M. J., & Karackattu, S. L. (2009, June 14-17) The researcher incubator: Fast-tracking undergraduate engineering students into research via just-in-time learning. 2009 ASEE Gulf-Southwestern Section Annual Conference, Waco, TX, United States.

Traum, M. J., Jones, T., Doher, J., Gurley, K., Magruder Waisome, J. A., Provost, A. L., & Mella-Alzazar, A. A. C. (2024). Virtual exchange embedded in a STEM summer camp improved United States high school students’ awareness of Filipino culture (Paper ID #40870). American Society for Engineering Education.

Traum, M., Provost, A., & Doher, J. (2022). STEMTank – Implementing online an engineering summer camp for underprivileged high school students in response to COVID-19. Opportunity Matters, 4, 86-101.

Weissman, S. (2024, February 7). New data signal flawed transfer process. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/institutions/community-colleges/2024/02/07/new-reports-show-fewer-half-transfers-complete

Zuckerman, A. L., Juavinett, A. L., Macagno, E. R., Bloodgood, B. L., Gaasterland, T., Artis, D., & Lo, S. M. (2022). A case study of a novel summer bridge program to prepare transfer students for research in biological sciences. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research, 4(1), 1122.

Lead image: STEMTank students and faculty

Adrienne L. Provost is Assistant Dean, Liberal Arts and Sciences; Matthew J. Traum is Senior Lecturer and Instructional Associate Professor, Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering; and Angela M. Kohnen is Associate Professor, Education, at University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida. Theresa J. Cothren is Academic Coach; Catherine Diaz is Educator, Science; Jodi Doher is former Academic Coach; Jacki L. Garcia is Academic Coach; and Jimmy Yawn is President, Soaring Saints Chapter, National Association of Rocketry, and Coordinator, Career Exploration Center at Santa Fe College in Gainesville, Florida.

Opinions expressed in Learning Abstracts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the League for Innovation in the Community College.