Victories in Information Literacy: A Library and Reading Department Collaboration

Montgomery County Community College (MCCC) publishes learning outcomes for each course offered. Reading department course outcomes include identifying and applying practical and efficient comprehension strategies for college-level texts. These outcomes are essential for academic success at the postsecondary level. Collaborative efforts between the Student Success Librarian and Reading coordinator and faculty began in 2018. In 2019, faculty in the Reading and Library departments developed a final course assignment intended to assess student learning for each course outcome.

The Assignment: Information Literacy Project

The Information Literacy Project (ILP) provides students the ability to apply skills and strategies learned throughout reading courses in an authentic library research assignment. Successful completion of the project assists postsecondary students in meeting learning outcomes, such as (a) understanding literal, inferential, and critical thinking processes while reading authentic and relevant material (Hairston-Dotson & Incera, 2020); (b) increasing knowledge about vocabulary development strategies for academic success (Nelson & Albarkry, 2024); and (c) incorporating information literacy (IL) skills into their college coursework (Badke, 2021).

Students apply before, during, and after reading strategies in authentic college-level contexts; incorporate cognitive and metacognitive reasoning strategies; increase understanding of developing academic vocabulary in context; and develop research skills. They access the MCCC digital library for practical application and specific research activities. To complete the assignment, students provide constructed responses to a series of prompts.

Reading faculty utilize the ILP as the final assignment in their courses and invite MCCC librarians to provide in-class instructional support for the project. Because the ILP assists students in meeting all course outcomes, aggregated statistics associated with this assignment give an overall measure of student learning in reading courses.

ILP Development

Reading faculty began using the ILP for assessment purposes. Since then, with the continuous improvement of course LibGuides and in consultation with the Librarian Liaison, the current ILP consists of two parts. For the lowest-level reading courses, students access the Get Help section of the MCCC Library web page to complete the first part of the project. In this section, students access the LibGuides, which provide information about specific topics (e.g., plagiarism, citations, and final exams) or courses at the college (e.g., REA 010/014). Research confirms the need to contextualize IL assignments and instruction (e.g., Zimmerer et al., 2018). In alignment with research and best practices in the field, the second part of the ILP supports students as they read the semester-long selection about a Holocaust survivor. The ILP, therefore, assists in building background knowledge and expanding student understanding of related World War II topics.

In the second-level courses, the ILP expands students' understanding of academic arguments by examining aspects of pro-con databases. Students compare features in pro-con research databases and then use them to explore a controversial topic. Using the databases, students are responsible for determining a topic, identifying a question, defining the issue, reading articles on both sides, exploring other possible resources, and citing sources correctly, according to the Modern Language Association (MLA) convention.

LibGuides

Student engagement with the libraries and associated services could have been more extensive; after a conversation with the Reading department Coordinator, we realized that we had underutilized LibGuides for the Reading department. LibGuides assist students and faculty in finding quick access to resources and are content focused to support learning in particular areas. Connecting the guides to the learning outcomes would support student learning and growth for college-level readers. Before our conversation, the Reading department guides—REA 010/014: Fundamentals of College Reading and REA 011/017: Pro and Con/Evaluating Sources—had 50-60 views per guide. With some creative thinking, we significantly changed the guides with student success in mind.

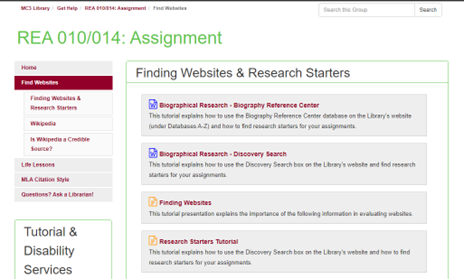

First, we agreed to change the name of the REA 010/014 guide. Although the courses are REA 010: Elements of Reading and REA 014: Vocabulary and Reading Comprehension Development I, the students knew the course as REA 010 or REA 014. We changed the name of the guide to REA 010/014: Assignment for clarity. Second, we needed clearer and shorter tutorials and guidelines for using the databases. Updated tutorials for the databases included how to evaluate resources and how to search for research starters. The guide was also cluttered with tabs for Creative Commons information and finding aids the students did not need for this class. Helpful resources added to the guide included campus support (e.g., Disability Services & Tutorial Services) and a new MLA citation guide (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: REA 010/014 Assignment LibGuide

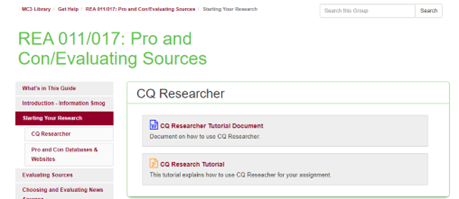

Third, we updated the REA 011/017 guide. This guide had fewer views and, therefore, needed more attention. Following the same structure as REA 010/014, we created new tutorials for CQ Researcher for student use. The tutorials provide step-by-step guidelines for using the database for future research. Since this is a higher-level class, we offered examples of evaluating resources and choosing new articles, along with an MLA citation style guide. These updates ensured clarity for students as well as improved connections between the IL content and Reading classes.

Figure 2: REA 011/017: Pro and Con Evaluating Sources Guide

Library Instruction

After updating the guides, we focused on IL instruction. When MCCC returned to campus after being virtual for two years, we jumped at the chance to revise the IL instructional formats for the Reading department. For the REA 010/014 class, students needed to find information on a historical figure or event from World War II. However, the activity for the class could have been more explicit and straightforward for students developing their reading skills. We opted to pare down the exercise by having students to (a) look at two databases instead of five, (b) search for main ideas and keywords related to their historical person, and (c) learn more about the importance of citations. This instructional update gave students a better understanding of how to search for and find information. We included tutorials/guidelines for searching in databases in the REA 010/014 guide.

The REA 011/017 instructional session required a minor update focused on clarification of databases available for students. The older IL exercise asked students to compare two databases; however, the libraries no longer subscribed to one of the databases listed. We removed the comparison option and asked students to concentrate on one database, then focused their attention on building their vocabulary and searching for information about a current event. The students divided the resources into categories (e.g., pro/con list, maps/graphs, chronology, and bibliography) and thought about how those resources would assist their research and how to use them. Using and thinking about the resources and keywords is essential because it connects to the research required for English 101, the next course students will take.

Results of the IL Collaboration Project

Assessment Data From Reading Faculty

Faculty submit assessment data on a semester-by-semester basis. The data include student learning as measured by demonstrated performance in published course learning outcomes. For the Reading department, faculty use the ILP and other assignments to determine if students consistently meet the published course learning outcomes. Aggregated assessment data since fall 2019 indicated pass rates of at least 70 percent of students and that ILP outcomes correlate with success rates for the course.

In addition to the aggregated statistics, anecdotal data provided noteworthy faculty observations. First, faculty observed high student engagement during the library instructional sessions. For example, students focused on the hands-on assignment, asked pertinent questions, and were generally satisfied with the class format. Faculty also noted that students exited the reading courses with an excellent grounding in college-level IL skills, thus preparing them for academic success in their next-level courses.

Assessment Data From Library Faculty

The guide update saw increased student use and supported faculty assignments. The REA 010/014: Assignment guide had 1,936 views and the REA 011/017: Pro and Con/Evaluating Sources guide had 2,353 views as of September 2023. With these increases, the reading guides became two of the most popular non-citation guides on the library’s website. The guides gave students a centralized spot for information that the Reading faculty could share easily.

With the success of new guides, we looked to connect to the learning outcomes in other ways. The assessment data showed that students knew how to find and cite scholarly resources via the library resources. This is a marked improvement from the assessment data from before 2019, which indicated that students needed clarification about which databases would be helpful for their research. There was also an increase in students and faculty from the Reading department coming to the library for IL sessions and appointments. The growth in these areas is critical because of the foundational connections to higher-level courses. The reading courses prepare students for the rigor of academic scholarship and the critical thinking skills needed to persist to completion. Library involvement in the process improved student knowledge and success.

Continuous Improvement

Our collaboration was successful for several reasons. First, faculty operated according to best practices in higher education assessment (Banta et al., 2009). For example, faculty designed and aligned a practical IL assignment with course learning outcomes and MCCC’s technological fluency core curriculum goal. Second, faculty were willing to accept feedback and critically reflect on improvements for student success, the needs of the Reading faculty, and the librarian's expertise within the institution's capacity. Continuous improvement through collaboration aligns with best practices in higher education assessment and embedding IL instruction within the disciplines (Badke, 2021; Banta et al., 2009). Through such collaboration, we have supported student learning by developing skills that will benefit them in upcoming academic courses and programs and, ultimately, for a lifetime of learning.

References

Badke, W. (2021). Research strategies: Finding your way through the information fog. iUniverse.

Banta, T. W., Jones, E. A., & Black, K. E. (2009). Designing effective assessment: Principles and profiles of good practice. Jossey-Bass.

Hairston-Dotson, K., & Incera, S. (2022). Critical reading: What do students actually do? Journal of College Reading and Learning, 52(2), 113-129.

Nelson, T. S., & Albakry, M. (2024). Navigating academic arguments: Teaching reporting verbs in transitional reading courses. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 54(3), 172-189.

Zimmerer, M., Skidmore, S. T., Chuppa-Cornell, K., Sindel-Arrington, T., & Beilman, J. (2018). Contextualizing developmental reading through information literacy. Journal of Developmental Education, 41(3), 2-8.

Amanda M. Leftwich, M.S.L.S., M.A., is Student Success Librarian and Assistant Professor, Libraries, and Dianna Sand, Ed.D., is Coordinator and Senior Lecturer, Reading, at Montgomery County Community College in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania.

Opinions expressed in Learning Abstracts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the League for Innovation in the Community College.