Combating Faculty Burnout Through Professional Learning Communities and Collective Self-Efficacy

Colleges and universities across the U.S. and beyond have recently been focused on efforts that promote a sense of student belonging or community (Ellard et al., 2022). However, students are not the only ones needing this connection. Faculty also need to feel a sense of belonging and community (Allen et al., 2021). Historically, educators worked within the confines of their office or classroom and had limited interactions with colleagues (Louis et al., 1996). The lack of interaction remains unchanged today and, in many ways, has been exacerbated by the pandemic (Leal Filho et al., 2021). Isolation and the rising use of technology for online meetings have resulted in decreased physical interactions with colleagues and increased feelings of loneliness, isolation, and burnout (Coffey, 2024; Zangaro et al., 2023).

As colleges focus on creating environments centered on promoting a community and sense of belonging for all, faculty needs must also be addressed. Facilitating learning communities is one method which has proven successful for supporting students’ sense of belonging, community, and well-being (Visher et al., 2008; Visher et al., 2012). When students are part of a learning community, they support and rely upon each other. Faculty learning communities work in a similar way (Cleary et al., 2023). Faculty connect with one another through a shared focus and bond. While there are many ways campuses can create learning communities, this article focuses on a learning community in which supporting students ultimately supports faculty.

The C4 Scholar Program

Nine years ago, a group of Ferris State University faculty and administrators concerned about the retention of students with developmental placements met to discuss possible interventions. From those initial conversations, the Cross-Curricular Career Community (C4) Scholar program was developed. The program is a multi-disciplinary, multi-semester learning community for students who need extra supports in English, math, and reading. The program is designed with the following supports:

- English 1 and 2 include weekly instructor-led labs and both developmental math courses offer twice-weekly workshops to complement regularly scheduled class meetings.

- Instructors meet bi-weekly throughout the academic year to discuss student issues and to make course adjustments based on student process; these meetings inform advising sessions and provide coherent strategies for promoting student success.

- Regular individual conferences are scheduled to review student progress, and the reading instructor provides both relational academic advising and counseling support.

- The pedagogy is student focused, with an emphasis on active learning strategies; group work is the principal means for building academic connections among the students in the cohort.

- In this long-term cohorting gradual release model, students take fewer classes together and receive fewer supports each semester.

The C4 Scholar program was created to close the retention gap between the college’s developmental and non-developmental student population. The structure of the program was inspired by the findings of The Learning Communities Demonstration (LCD), which examined the effects of one-semester interventions on student success (Visher et al., 2008). The project ultimately revealed that after the short-term interventions ended, the modest academic gains generally dissipated (Visher et al., 2008; Visher et al., 2012). In an effort to push beyond these limited gains, C4 courses extend past one semester and the program includes best practice components designed to support students, including intensive advising, course support and acceleration, mentoring, and long-term cohorting.

Another essential program component—bi-weekly meetings for faculty—is designed to provide ongoing student support and assessment (Cavner Williams et al., 2020). These meetings function as a faculty learning community in which instructors from the math, English, and reading departments convene to discuss how best to support C4 Scholar program students. The discussions center on best practices and challenges related to student learning. Ultimately, these collaborative and cross-disciplinary conversations lead to new approaches to teaching and problem-solving, which supports student success, as students are essentially triaged by a group of experts (Cavner Williams et al., 2024). However, an unintended consequence of coming together to support students is that faculty are also supported, both professional and emotionally.

Every other week, faculty meet to talk about how the students are doing academically and socially. They discuss the stresses of the last couple of weeks, and, most importantly, have a chance to celebrate successes. In other words, a couple of times each month faculty gather to brainstorm and support one another. Support is important for all educators, especially those who work with students requiring assistance, as there is often added stress for the educator taking on the responsibility of addressing additional student needs (DeShazer et al., 2023). Although at times this stress is related to extra work, faculty investment in each student’s success can also result in emotional stress (Goddard et al., 2000; Goddard et al., 2004). The C4 Scholar program faculty learning community has been in place for almost a decade to combat this toll on faculty mental health.

Faculty Collaboration and Data-Driven Decisions

A strong faculty community allows for a shared commitment to student success. These communities are beneficial for faculty because they provide opportunities for collaboration and a natural opportunity for mentorship (Loughland & Nguyen, 2020). Depending on the topic or situation, a faculty member can find themselves in the mentor or mentee position. In either case, the faculty learning community provides opportunities for shared best practices and developing cross-disciplinary approaches to teaching. It is also helpful to have a team analyzing student success data and examining trends so that patterns are recognized earlier and the chance of overlooking an issue is lessened. Additionally, a new perspective helps faculty to expand their intervention toolbox. This atmosphere of support gives faculty time to discuss challenges related to teaching and student learning (Liu & Yin, 2023), which not only assists students and contributes to their success but also contributes to the well-being of the educators as part of a community. Research shows that building thriving communities helps to foster improved mental health and well-being for everyone (Cleary et al., 2023). When community members feel connected and have safe places to gather, they experience less stress and anxiety.

Community Creates Collective Self-Efficacy

The well-being of faculty is closely linked to their ability to support students effectively, which is connected to what Klassen and Tze (2014) refer to as teacher self-efficacy. Teacher self-efficacy has been linked to positive outcomes, such as reduced stress, increased job satisfaction, and continued engagement with professional learning interventions (Schiefele & Schaffner, 2015); it has also been adapted and extensively validated as an instrument to measure teachers’ perceived sense of collective efficacy (Loughland & Nguyen, 2020; Gooddard et al., 2000, 2004). What does this mean for educators? It means that teachers’ sense of efficacy as a team has profound impact on the learning outcomes of the students they teach (Loughland & Nguyen, 2020). Professional learning communities provide space for faculty to share ideas, experiences, challenges, and professional and emotional support. This sense of connectedness mitigates feelings of isolation and fortifies resilience among faculty members. Professional learning communities are a high-impact teaching practice (Kuh, 2008). When faculty engage in professional learning communities, they are more likely to remain engaged and motivated and to provide a high-quality education for students (Goddard et al., 2000; Goddard et al., 2004). C4 Scholar program faculty members often discuss the importance of gathering every other week and the benefits gained from sharing ideas and collaborating rather than sitting alone in their offices trying to figure out how best to support their students.

Implementing a Faculty Learning Community on Your Campus

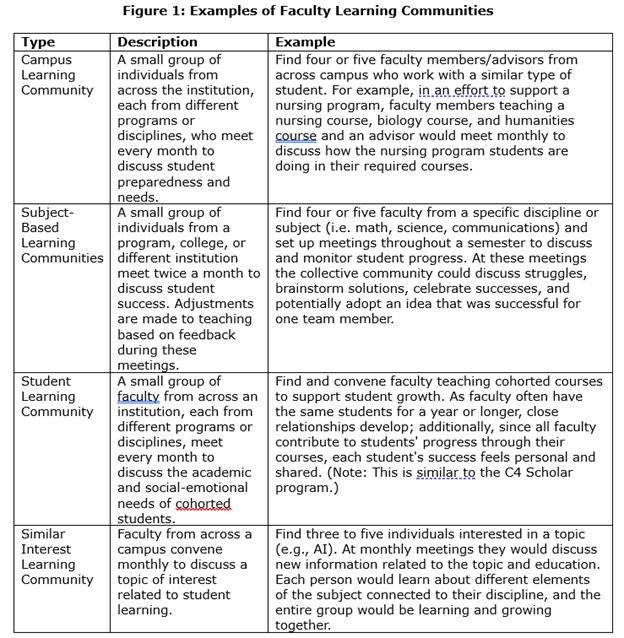

There are a variety of ways to implement a faculty learning community on a college campus (see figure 2 for examples). Faculty could collaborate with a group of friends, work within a department to support students who struggle in a particular program, or collaborate across disciplines or campuses, which research shows “makes us smarter” because we are working with a diverse set of people (Phillips, 2014). Institutions could implement their own version of Ferris State University’s C4 Scholar program. Whichever method is chosen, developing a learning community is an essential way to combat faculty burnout (Cleary et al., 2023) Building a thriving community and sense of support and belonging may help a colleague or friend and can foster positive mental health and well-being for everyone involved.

Conclusion

Faculty learning communities are vital to the success of both students and faculty. By providing a platform for collaboration and reciprocal support, these communities help create an environment in which instructors thrive, and students benefit from improved learning experiences. Ensuring that faculty have the connections and resources they need is key to promoting academic success and maintaining a healthy, active, and dynamic educational environment.

References

Allen, K. A., Kern, M. L., Rozek, C. S., McInereney, D., & Slavich, G. M. (2021). Belonging: A Review of Conceptual Issues, an Integrative Framework, and Directions for Future Research. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1883409

Cavner Williams, L., Conley, K., Pavletic, H., & Weller, K. (2020). C4 scholar program: Promoting success through accountability for at-risk students. Innovative Higher Education, 45(3), 221-235.

Cavner Williams, L., Conley, K., Courtright Nash, D. Pavletic, H., Weller, K., & Zimmer, M. B. (2024). Transformation of instruction to enhance student success. Journal of College Literacy and Learning, 49, 76-84. https://storage.googleapis.com/wzukusers/user-20714678/documents/c0f6903e98354fa390823c6438d3bad3/Program%20Transformation.pdf

Cleary, S., O’Brien, M., & Pendergast, D. (2023). Exploring the links between psychological capital, professional learning communities, and teacher wellbeing: An examination of the literature. Education Thinking, 3(1), 41-60. https://pub.analytrics.org/article/13

Coffey, L. (2024). Faculty members are burned out and technology is partly to blame. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/teaching-learning/2024/08/26/report-finds-professors-are-burned-out-thanks

DeShazer M. R., Owens J. S., & Himawan L. K. (2023, May 17). Understanding factors that moderate the relationship between student ADHD behaviors and teacher stress. School Mental Health, 1-15. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10191405

Ellard, O., Dennison, C., & Tuomainen, H. (2022). Review: Interventions addressing loneliness amongst university students: a systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 28(4), 512–523. https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/camh.12614

Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Hoy, A. W. (2000). Collective teacher efficacy: Its meaning, measure, and impact on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 479-507.

Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K. & Hoy, A. W. (2004). Collective efficacy beliefs: Theoretical developments, empirical evidence, and future directions. Educational Researcher, 33(3), 3-13.

Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. C. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59-76.

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Leal Filho, W., Wall, T., Rayman-Bacchus, L., Mifsud, M., Pritchard, D. J., Lovren, V. O., Farinha, C., Petrovic, D. S., & Balogun, A. L. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 and social isolation on academic staff and students at universities: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1213. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11040-z

Liu, S., & Yin, H. (2023). Opening the black box: How professional learning communities, collective teacher efficacy, and cognitive activation affect students’ mathematics achievement in schools. Teaching and Teacher Education.

Loughland, T., & Nguyen, H. T. M. (2020). Using teacher collective efficacy as a conceptual framework for teaching professional learning – A case study. Australian Journal of Education,64(2), 147-160.

Louis, K. S., Marks, H. M., & Kruse, S. (1996). Teachers’ professional community in restructuring schools. American Educational Research Journal, 33(4), 757-798.

Phillips, K. (2014). How diversity makes us smarter: Being around people who are different from us makes us more creative, more diligent and hard-working. Scientific America. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-diversity-makes-us-smarter

Schiefele, U., & Schaffner, E. (2015). Teacher interests, mastery goals, and self-efficacy as predictors of instructional practices and student motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 42, 159-171.

Visher, M. G., Wathington, H. D., Richburg-Hayes, L., & Schneider, E. (2008). The learning communities demonstration: Rationale, sites, and research design. An NCPR Working Paper. National Center for Postsecondary Research. https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_566.pdf

Visher, M. G., Weiss, M. J., Weissman, E., Rudd, T., & Wathington, H. D. (2012). The effects of learning communities for students in developmental education: A synthesis of findings from six community colleges. National Center for Postsecondary Research. https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/LC%20A%20Synthesis%20of%20Findings%20FR.pdf

Zangaro, G. A., Rosseter, R., Trautman, D., Leaver, C. (2023, September-October). Burnout among academic nursing faculty. Journal of Professional Nurses, 48, 54-59.

Kristin Conley is Chair and Associate Professor, Interdisciplinary Studies, at Ferris State University.

Opinions expressed in Learning Abstracts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the League for Innovation in the Community College.