Marching Forward: Veterans, CLEP, and Student Success

When I first started working in a college testing center in 1999, one of the first things I had to do was to become College-Level Examination Program (CLEP) certified. I had no idea what that meant exactly, but it was something that needed to be done so I did it. Little did I realize at the time how much interest I would eventually have in CLEP exams and the overall impact on student success.

Today, over 1,700 college testing centers administer CLEP exams, and the exams are accepted at roughly 2,900 colleges and universities (The College Board, 2012). According to the College Board, approximately 183,000 CLEP exams were administered in the academic year 2011-2012, with over seven million exams taken by students since the inception of CLEP exams in 1967. This credit-by-examination program serves a diverse group of students and validates knowledge learned through independent study, on-the job training, or experiential learning by translating that learning into college credit.

CLEP Test Development

As opposed to an admission or placement exam that tests for aptitude, a CLEP exam is designed to test for mastery of content. For that reason, over 600 faculty members from schools across the nation contribute to the development of and standard setting for every CLEP exam (The College Board, 2012). Standing faculty committees oversee ongoing test development, shape content, and review data to make sure each exam truly reflects the content a student would encounter in the comparable course. Standing test development committees consist of three or four faculty members, each of whom teaches the relevant course and oversees ongoing test development. In addition, CLEP exams undergo two dozen reviews and quality assurance steps before being released for public use. Educational Testing Service (ETS) is responsible for the design, development, and scoring of CLEP test items.

Which Students Take CLEP?

Among the groups and individuals who regularly take the tests are (Seaver & Zorka, 2013):

- First-year students looking to accelerate their college path

- Adults returning to college

- Transfer students

- Students struggling to finance their educations

- Home-schooled students

- International students who need to translate their overseas credit

- Students who are fluent in Spanish, French, or German

- Juniors or seniors who have not met lower-division requirements

- Veterans

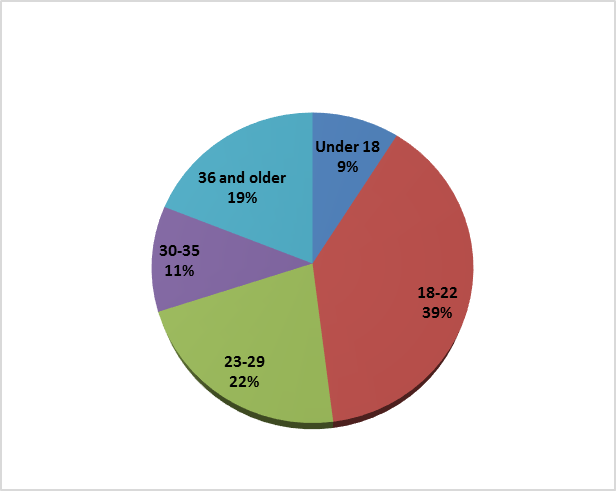

As evidenced in Table 1 (Maher, 2011), the age range for persons taking CLEP exams is equally as diverse. The highest percentage represents traditionally aged college students (18-22), but the next highest group is the nontraditional, returning to college age cohort (23-29). This group likely also contains the veteran demographics referenced above.

Table 1: Exams Administered to National Candidates, 2010-2011

(Maher 2011. Used with permission.)

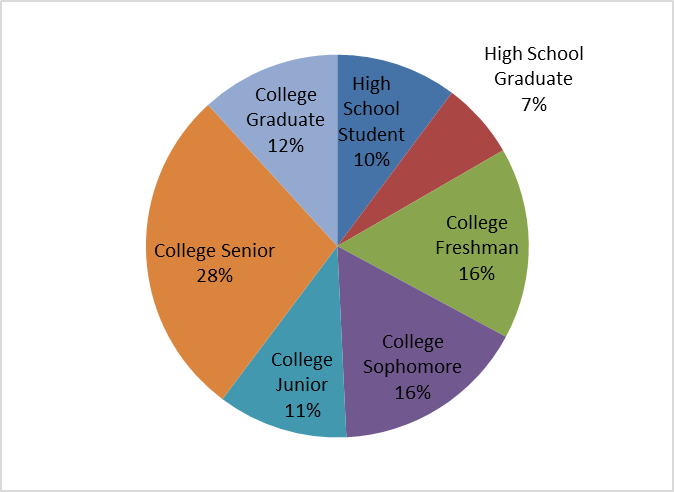

Table 2 (Maher, 2011) gives insight into the actual education level of test takers. Not surprisingly, juniors or seniors who have not met lower-division requirements make up the highest group percentage (39 percent combined). First-year students looking to accelerate their college path and transfer students (traditionally college freshmen and sophomores) make up 32 percent of CLEP exam takers.

Table 2: Exams Administered to National Candidates, 2010-2011

(Maher 2011. Used with permission.)

The College Board reports that approximately 26,000 Spanish Language exams were administered in 2010-2011 (Maher, 2011). That total is greater than the next three most popular exams (Analyzing and Interpreting Literature, English Composition, and College Algebra) combined. The reasons for this include factors such as the amount of credit granted for Spanish and the greater number of Spanish speaking and first-generation students entering the nation's colleges and universities.

CLEP and the Military

In February 2013, a colleague and I had the opportunity to make a presentation regarding military personnel and prior learning assessments (PLAs)--namely CLEP--at the Military Symposium for Higher Education, hosted by the University of Louisville. During that presentation, we referenced a quote from Dr. Anthony Dotson, Veterans Resource Center Coordinator at the University of Kentucky. Much to our surprise, at the end of the presentation, Dr. Dotson (who was in attendance), stood up and offered even more insight into his use and advocacy of CLEP for military students. He stated:

I'm a huge proponent of CLEP. In fact, I CLEPed my freshman year of college. I encourage all incoming veterans to consider taking CLEP prior to their arrival at UK, especially if they have not left active duty, as the exams are at no cost to them. CLEP can allow these nontraditional students to enter college a little better prepared and not as far behind their traditional student peers.

CLEP exams are available to eligible military personnel to assist them in meeting their educational goals. The Defense Activity for Non-Traditional Education Support (DANTES) funds CLEP exams (one attempt per title) for eligible military service members and civilian employees, including

- Military personnel (active duty, reserve, National Guard): Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, National Guard(s), and their designated Reserves;

- Spouses and civilian employees of: Air Force Reserve, Air National Guard, Army National Guard, Army Reserve, Coast Guard (active and reserve); and

- Department of Defense Acquisition personnel.

Military veterans can receive reimbursement for CLEP exams and testing center administration fees by completing and submitting the Application for Reimbursement of National Exam Fee Form 22-0810.

To truly understand student success, it's usually best to understand the situation of a particular student. One such student is Carlos Paillacar. Carlos retired from the Coast Guard at age 46, after 21 years of service, to pursue his education. He stated in a TV interview, "Before I retired, I said to myself, 'Well I speak Spanish. I should take the CLEP in Spanish'" (Univision, 2012). He received 12 credits for successfully passing the CLEP Spanish exam in the summer of 2012 (and an additional 13 credits from Miami Dade College as part of his PLA in the area of Photography). With credit in hand, he enrolled at Barry University as a sophomore with 25 credits and $12,000 in savings, thanks to CLEP. He added, "Barry took me basically as a second year transfer student with 25 credits. It basically saved me a year of education" (Univision, 2012).

Hispanics and the Military: The Educational Connection

Carlos Paillacar is not alone. Hispanics have been an important part of the American military for decades. Nearly 214,000 Hispanics are currently serving in the U.S. armed forces, with more than 157,000 (or 11.4%) concentrated among our active-duty military (Sanchez, 2013). In 2011, 16.9 percent of all new recruits were Hispanic. On a national level, service members of Hispanic ethnicity and nonwhite races (including multiple races) are projected to make up an increasing share of the total veteran population, with an even higher share for female veterans. One of the traditional reasons Hispanics join the military is a lack of opportunities to pursue other careers since education is too expensive for many working-class people (Sanchez, 2013).

The cost of higher education as a barrier to family-wage careers can partially be decreased by utilizing CLEP. From 2009 to 2010 there was a 24 percent increase in college enrollment among Latinos (Cardenas & Kerby, 2012), with a large number being former military personnel. Much like Carlos Paillacar, these students have amassed a great amount of skill and talent that can lead to college credit through CLEP exams. Utilizing not just language skills, but other skills that can be measured via prior learning, can be that crucial link in the educational chain for Hispanics in the military.

CLEP Research and Student Success

College students in general benefit greatly from the CLEP exam, and in many ways. In a 2010 study of Florida public institutions (Barry, 2011), preliminary results for CLEP students found that

- CLEP students graduate in less time than non-CLEP students;

- CLEP students have higher GPAs than non-CLEP students; and

- Students earning credit through CLEP perform better in subsequent English courses than non-CLEP students.

Additionally, the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL), in cooperation with the Lumina Foundation for Education, published a study entitled Fueling the Race to Postsecondary Success in March of 2010. This study, which surveyed PLA/CLEP data from 48 nationwide institutions, found that in the areas of college persistence (i.e., retention), time to degree, and overall degree attainment (within 7 years), PLA students completed course and degree requirements at a pace that was twice, and in some cases as much as three times greater, than their non-prior learning counterparts.

A separate study released by CAEL (Klein-Collins, 2011) reported that Hispanic PLA students earned bachelor's degrees at a rate that was almost eight times higher than that of Hispanic non-PLA students. Furthermore, African American PLA students earned bachelor's degrees at a rate that was almost three times higher than that of African American non-PLA students. These findings suggest that CLEP/PLA could be a potentially important strategy for helping underserved or disadvantaged student populations to succeed in completing postsecondary degrees, and at a substantial cost savings.

While the Florida and CAEL/Lumina data is certainly thought provoking, I wanted to see if those outcomes would be duplicated in regard to my own test takers at North Lake College (NLC). In the summer of 2009, I recruited Spanish speaking, new-to-college students to take the Spanish Language CLEP exam. In the fall of 2009, 54 high school and first time in college students took the Spanish Language CLEP test at the NLC Testing Center in Irving, TX (Seaver & Zorka, 2013). Of the 54 students who tested, 47 entered college (87 percent). Two years later, in the fall of 2011, the number of the CLEP students retained was 43, or 92 percent. By contrast, the retention percentage of the 1,196 first time in college students at NLC in fall 2009 was only 58 percent. The overall GPA of those 47 CLEP students who were retained after two years was 2.93 (Seaver & Zorka, 2013), while the overall NLC GPA for students who entered college at that same time was 2.18. Much like the outcomes generated from the Florida study, students who took advantage of CLEP as a PLA succeeded at a higher rate than the average student.

Communicating the CLEP Opportunity and Its Benefits

As in any other industry or entity, communication in college is essential to a successful education. Similarly, a lack of it can hurt all involved. According to Veney, O'Geen, and Kowalik (2012):

Where campus policies and practices to assist nontraditional students do exist, those individuals who serve this population--and nontraditional students themselves--are largely unaware of them. If campus policies and practices that support nontraditional students were known to staff and students, they doubtless would serve to increase nontraditional students' retention and academic success. (Findings section, para. 3)

In other words, there are several ways colleges and university personnel can maximize the benefits of CLEP, and that maximization starts as soon as the student arrives on campus.

- Admissions and registration offices can inform prospective and incoming students about CLEP by including CLEP policy information in new student orientation packets, and making sure up-to-date CLEP credit policy is in the college catalog and other publications for students and parents. Keep in mind that CLEP maximizes enrollment by allowing students to advance to more challenging courses, opening availability in introductory courses.

- Faculty and advisors should advise students to include CLEP in their academic plan to satisfy general education and credit transfer program requirements. Efforts can include making students aware of the college's credit-by-exam policy, providing CLEP policy information at events for transfer students, and helping students to prepare for exams with necessary practice information.

- Adult and veterans offices can advise students about how CLEP fits in their degree programs, and let veterans know that they may be reimbursed for CLEP exam fees. Staff should make sure students know the cost of CLEP versus that of a traditional course, inform traditional and nontraditional student organizations and veterans groups about the college's CLEP policy, and assist students in completing Form 22-0810 for veteran reimbursement, as necessary.

- In addition to administering the actual CLEP exams, testing centers can provide information to students about the CLEP registration process. Testing centers can also bring in examinees who are not currently students at the institution. According to a recent survey of CLEP candidates (The College Board, 2012), 62 percent of students not currently enrolled say that the CLEP policies of the institutions they were considering would affect their decision to enroll. According to Elinor Azenberg, Director, Reentry Programs at New York University, "CLEP is an important recruitment tool for our institution. When students hear that we give credit for CLEP exams, they are interested in exploring studying here" (The College Board, 2012, p. 17).

CLEP Benefits Students

In a 2011 College Board survey of CLEP students (The College Board, 2012), 91 percent said CLEP made a difference in their ability to complete their degrees, and 70 percent said CLEP made a difference in their ability to finance their degrees.Students who earn college credit via CLEP are more likely to persist through college, which creates higher college retention rates. Those students are also likely to have higher GPAs when they graduate or transfer, leading to increased student success. In today's work of decreased state funding, lower retention and graduation rates, and increased government scrutiny, it is imperative that we in higher education use all of the tools available to create strong student success and allow students to achieve the dream of a college education. CLEP is such a tool.

References

Barry, C. L. (2011). A comparison of CLEP and non-CLEP students with respect to time to degree, number of school credits, GPA, and number of semesters. Research by Henson, R.New York: The College Board. Retrieved from http://professionals.collegeboard.com/profdownload/CLEP_henson_research_feb_2011.pdf

Cardenas, V., & Kerby, S. (2012). The state of Latinos in the United States. Washington DC: Center for American Progress. Retrieved from http://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2012/08/pdf/stateoflatinos.pdf

The College Board. (2012). Academic success in higher education. New York: Author. Retrieved from http://media.collegeboard.com/digitalServices/pdf/clep/12b_5569_CLEP_Brochure_WEB_120420.pdf

Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. (2010). Fueling the race to postsecondary success: A 48-institution study of prior learning assessment and adult student outcomes. Chicago: Author. Retrieved from http://www.cael.org/pdf/PLA_Fueling-the-Race.pdf

Klein-Collins, R. (2011, April). Underserved students who earn credit through prior learning assessment (PLA) have higher degree completion rates and shorter time-to-degree (Research Brief). Chicago: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. Retrieved from http://professionals.collegeboard.com/profdownload/CAEL_research_april_2011.pdf

Maher, M. (2011, September). CLEP 101: What every CLEP administrator needs to know. Presented at the 12th annual National College Testing Association conference, Making Waves in Testing, San Diego, CA. Retrieved from http://www.docstoc.com/docs/158564933/Session-Title-Here---the-National-College-Testing-Association#

Sanchez, E. L. (2013, January 1) U.S. military, a growing Latino army. NBCLatino. Retrieved from http://nbclatino.com/2013/01/01/u-s-military-a-growing-latino-army/

Seaver, K., & Zorka, A. (2013, February). Marching forward: Veterans, CLEP, and student success. Retrieved from http://stuaff.org/veterans/vetpresentations2013/seaver_zorka.pdf

Univision (Producer). (2012, October 8). Nunca es tarde para estudiar. On Premier Impacto. Retrieved from http://noticias.univision.com/primer-impacto/videos/video/2012-10-09/es-el-momentoestudiarstudygo-to-school/embed

Veney, C., O'Geen, V., & Kowalik, T. F. (2012, January). Role strain and its impact on nontraditional students' success. American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers Strategic Enrollment Management Source. Retrieved from http://www4.aacrao.org/semsource/sem/index0790.html?fa=view&id=5292

Opinions expressed in Innovation Showcase are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the League for Innovation in the Community College.