Framing Mobile Initiatives to Measure Impact

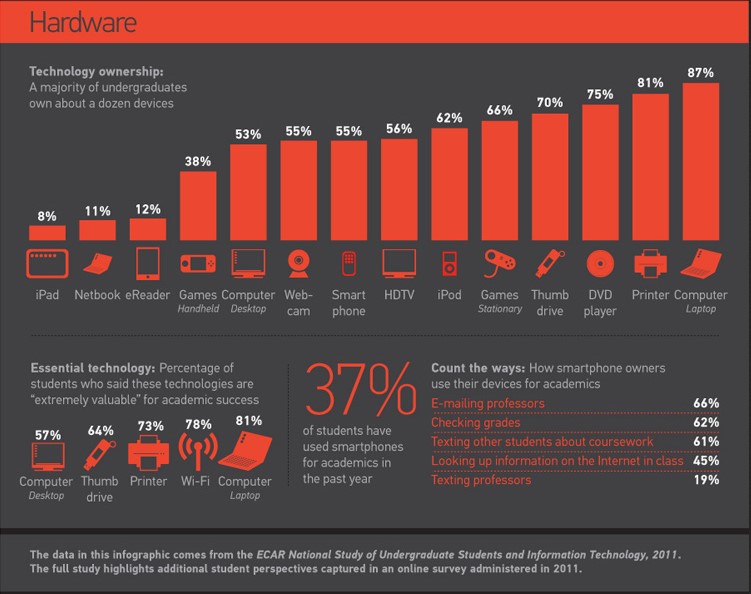

There is no shortage of data illustrating the proliferation of mobile devices and mobile activity in the general population. This diffusion of devices, applications, and activity extends to the teaching and learning community, right down to the classroom level (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Student Ownership of Technology Devices

Yet, mobile technologies, and even more so, mobile pedagogies are still considered very much an emerging area in higher education. It is critical that some sort of measurement strategy accompany our experimental and pilot programs. But measuring the ability of mobile teaching and learning initiatives to support such amorphous things as student learning, student engagement, and additional time on task can prove to be very challenging.

In this paper, I propose a set of frameworks, drawn from the literature, to begin identifying and deconstructing the components we might measure in our mobile learning initiatives. It is important to distinguish between the components we choose to measure and the way in which we measure them. Here, the focus is on the desired mobile learning experience itself, on which we'll want to be able to report after our work has concluded. For instance, we may engage in direct observations to understand how an iPad is being used in class to solve a problem. Observation is the method in this example while problem solving is part of the pedagogical framework that we've developed for the initiative. A well-developed framework and effective measurement strategy are important considerations, whether you are embarking on a mobile learning project for the first time or are in your third or fourth phase of the project.

Before considering a measurement strategy, I recommend taking one step back to categorize the kind of mobility work in which your organization is involved. In their literature review, Naismith, Sharples, and Ting (2005) propose these six classifications and examples for mobile learning:

- Behaviorist: activities promoting learning as a change in learners' observable actions. This category describes learning that happens or is supported by the reinforcement of an association between a particular stimulus and a response.

- Constructivist: activities in which learners actively construct new ideas or concepts based on both their previous and current knowledge. In this category, learning is an active process.

- Situated: activities promoting learning within an authentic context and culture. In this category, learning can be enhanced by ensuring it takes place in a real-world context. An example here could be context-aware applications because they draw on surrounding environments to enhance the learning activity.

- Collaborative: activities promoting learning through social or other interaction. Collaborative learning is based on the role of social interactions in the process of learning, and mobile devices offer new opportunities to engage in collaborative learning.

- Informal and lifelong: activities that support learning outside a dedicated learning environment and formal curriculum. This category includes activities that are embedded in everyday life, thus emphasizing the value of mobile technologies in supporting them.

- Learning and teaching support: activities that assist in the coordination of learners and resources for learning activities. This category includes activities or applications that are not instructional in nature but that support instruction and thus learning. For example, access to the learning management system, schedules, library resources, or student support services.

Using these categories can help us further clarify existing current mobile learning efforts and also suggest opportunities for future work. For instance, it is not uncommon for many institutions to begin their mobility work in the learning and teaching support category (for example, providing mobile access to course schedules), sometimes outside an instructional context. But doing so builds tolerance and understanding of mobile applications with our students, a tolerance that can be leveraged for learning in the classroom.

Another way to organize institutional mobile learning activities is by the degree to which they are integrated into the curriculum. I propose three levels:

- Level 1: service-related mobile content (e.g., access to the schedule or course offerings, library resources and services, campus tram whereabouts)

- Level 2: generic mobile instructional applications (e.g., use of student response systems, Twitter, or the learning management system)

- Level 3: discipline-specific, customized mobile learning (e.g., mobile applications or tools that are developed to support a particular set of learning objectives within a discipline)

As noted earlier, many institutions begin development of mobile content and resources in areas that support students in a non-instructional way, as described in level 1. Others support learning through the use of mobile applications that are openly available at little or no cost to the user (level 2). Some examples of this include backchannel tools like Twitter or Poll Everywhere. Another example might be enabling students to access information (grade book) or content (assignments, readings) in the mobile-enabled learning management system. These uses are distinguished by the fact that they can be used by any discipline and may be applied in a variety of ways. Level 3 describes the use of mobile applications and devices to support specific discipline-based learning objectives. In other words, this level supports the development of pedagogies that specifically make use of the affordances of mobile learning. For instance, Carleton College developed a mobile digital flashcard program to support the educational goal of helping language learners expand their French vocabulary--an area of persistent need (Born & Nixon, 2012). Level 3 activity is more costly but often yields the highest returns in the areas of improved learning, increased student engagement, and additional time on task. Institutions do not typically begin their mobile work here, but when they do this kind of work, they collaborate with instructors, instructional designers, and technology developers to create customized mobile software and applications.

Organizing mobile activities and efforts according to the levels or categories described above can support planning and strategy by understanding where current mobility work is taking place and by helping institutions set goals for where they want to go in future phases of mobility. The development and use of frameworks to measure activity at each level is, of course, critical in moving forward and informing those directions.

Frameworks for Measuring Impact

In this section, I draw from four studies or cases of institutional work in the area of mobile learning. Each case offers some ideas and guidelines for the components of a mobile experience to consider before developing or launching a pilot or evolving an existing project.

Case 1: Identifying Focus Areas

Because mobile teaching and learning is still an emergent area, many studies are exploratory in nature. In other words, they don't establish any specific criteria for measurement or identify areas for examination. They simply insert technology and applications into the learning environment and observe how instructors and learners are using them. While it's fine and even desirable to have an exploratory component in a pilot, it's important to identify areas of focus or outcomes that you want to report on when the study is finished.

In their study on assessing mobile learning in a large blended classroom, Wang et al. (2008) identified several areas for analysis:

- Student enjoyment and learning

- Student interaction with other students

- Student interaction with instructors

- Impression of the mobile learning environment

- Effect on study habits

The researchers designed survey questions (see study for additional information on the surveys) organized around measures of activity, efficiency, outcomes, and organization. They also set out to measure student satisfaction, level of interaction (student-student, student-instructor), and sustainability of student participation in mobile learning activities.

After collecting and analyzing the quantitative and qualitative feedback, they established seven reliable evaluative dimensions for the study of mobility's effects on learners: overall satisfaction, course organization, course activities, student interaction, instructor interaction, relationship to content, and sustainability. Each of these is described in detail in the study, which provides an excellent framework for a mobility study.

Case 2: Challenges and Goals

Identifying areas for study is only the first step in evaluating mobile learning. Vavoula and Sharple (2008) suggest several challenges and opportunities and further contribute to our framework:

- Capturing learning contexts and learning across contexts: Learning that happens in a variety of spaces, inside and outside a classroom, is more challenging to capture than that which is situated in a fixed, physical learning environment. "This study suggests that mobile learning research attempt to capture the location of learning and the layout of the space (where); the social setting (who, with whom, from whom); the learning objectives and outcomes (why and what); the learning method(s) and activities (how); and the learning tools (how)" (p. 2).

- Identifying learning gains: Many mobile learning studies set out to improve student learning but struggle to isolate the effect of mobility on learning and to define gains in learning. In other words, how will you know students learned more because of a mobile application, and how will you measure how much more they learned as a result? This study suggests we be very specific about what we are looking for and identify a few behaviors--for example, where learners show responsibility for and initiate their own learning (e.g., by writing), are actively involved in learning (e.g., spending additional time on a task), or make links and transfer ideas and skills (e.g., by comparing information).

- Tracking behavior: Although rare, some studies monitor student activity on mobile devices with the use of tracking software. This can be unreliable and present ethical issues. An alternate approach is to ask students to contribute to a daily or weekly journal about their mobile learning experience: what they did, what went well, what was challenging, and so forth. Doing so can help to assess the dimensions established in case 1 above.

- The technology itself: Mobile technology today spans a variety of devices, from the small flip phone to tablets and even netbooks. Studies should include some component related to the usability of the devices themselves and also to the extent to which they are integrated into the learners' technology constellation. In other words, how well do the devices and the applications used work with other technologies used on a daily basis. Is the experience seamless, cumbersome, or incompatible? How could it be improved?

- The big picture: Mobile learning has the potential to expand the learning environment well beyond the walls of the institution. Vavoula and Sharples suggest the use of Price and Oliver's impact studies: anticipatory, ongoing, and achieved. "Anticipatory studies relate to pre-intervention intentions, opinions, and attitudes; ongoing studies focus on analyzing processes of integration; and achieved studies are summative studies of technology no longer novel" (p. 6) This phased approach is valuable as we plan the future phases of our mobile studies. While today's studies may explore integration with existing technologies and basic use, tomorrow's studies may look at applications tailored to learner environments and needs. As the technology evolves and matures, so should our studies.

- Formal and informal learning: Mobile technology is blurring the lines between formal and informal learning as it enables students to access and interact with their learning environment and networks anywhere, anytime. Students will have to help us understand these contexts as they continue to evolve into highly personalized environments. As these come into focus, we'll better understand how and where support is needed.

Case 3: Mobile Learning and Instructional Design

Traxler and Kukulska-Hulme (2005), based on their extensive review of mobile learning initiatives, suggest several characteristics of a good mobile learning experience. In this list, we could supplant mobile technology with any technology, which demonstrates these are universal instructional design principles. As such, these could be used to develop a rubric to measure our local mobile learning work. It should also be noted that this list is particularly relevant when a technology is new or emergent and may be less so as it evolves and becomes increasingly ubiquitous.

- Proportionate. What is the proportion of time spent learning and applying the technology with the actual learning experience or learning benefit? A cost/benefit analysis is suggested, which will, to some extent, depend on the tools (device and applications) you use and the extent to which students are familiar with them.

- Fit. How appropriate is the mobile technology to the learners, to the learning, and to the course delivery mode? Is there a good fit between the technology and the desired outcome, between the technology and the tools students already have or know, between the technology and the style of the instructor? Is the technology well integrated into the students' personal learning environment?

- Alignment. To what extent are the learning goals mapped to the technology's affordances? It might be helpful to make these connections for students, especially if the technology or its application is experimental.

- Unintended results. Since mobile learning is still relatively new, it will be useful to find a way to identify unexpected outcomes--a qualitative approach will likely be most effective. Doing so will help inform future phases of mobile initiatives.

- Consistency. How consistent is the technology's application (and results) across learners? Is the use or application reliable? How consistent is it across devices and technologies used?

These five components can be integrated into a mobile learning framework and into the very design of the initiative. They can be fashioned into a rubric to be used as we design, evaluate, and evolve our pilots.

Case 4: The Student Experience

In a case study of a medical school's mobile learning experience, Nestel et al. (2010) highlight several findings that are worth considering as we build our mobile initiatives. The institution in the study offered a graduate medical program where students largely spent their first year on campus, while the remaining three years were spent almost entirely in clinical settings. All students were issued a mobile device at the start of the program and worked inside a virtual learning environment that made use of two main teaching and learning tools, Blackboard and Interlearn, for course management and facilitation of interaction online, along with various other licensed software. There were 57 students in the entering cohort for the case study, and through student questionnaires and interviews, the study sought to address two questions: In what ways does mobility support learning, and what areas need development?

This institution sought to enhance students' learning experience through the use of mobile technology to provide access to the Internet, software, and information repositories and also to enable information sharing within and between cohorts. In this case, students had access to more than 10 different sources (e.g., lecture notes, problem-based learning materials, external weblinks, summative assessments). These goals are not uncommon in mobile initiatives, and many institutions will provide students with a significant amount of digital content to support their learning.

Students in the study offered a few suggestions for improvement. They asked for more robust resources and for more electronic learning resources (especially audiovisual resources), along with more flexibility in accessing the materials. Since there was so much content, they felt they would have benefitted from guidelines and support on managing their virtual learning environments.

This case offers several key questions for our consideration:

- What previously unavailable digital (on mobile devices) content and resources will we make available to students?

- How will students be introduced or oriented to the content and the environment within which it resides?

- Where will this content reside, and how will it be organized? In other words, will the materials be held in a single repository; will there be a portal to access content from a variety of sources? As the volume of content increases, we need to be mindful of how the learning environment is structured and how that structure enables learning. If the environment is cumbersome and complex, students are not likely to use it.

- How will students manage their resources? How are students able to interact and engage with the content? Are they able to annotate, download, share, or highlight the content? How long are they able to access the materials, from how many devices, and in what ways?

Some of these issues can and should be addressed together with students. Students can help us create or understand their learning environments and the features they need to make the best use of them. As mobile technologies enable the proliferation of content and resources, effective information management becomes critical.

Implications for Planning

Earlier in this paper I noted the distinction between the components we wish to measure and the way in which we go about measuring them. Once we have developed the components of the mobile experience or the framework we can then explore approaches for measurement. For instance, we might determine the best way to identify unintended results is through focus groups, live observations, and journal analysis. Alternatively, you might measure the impact of a particular mobile technology on student comprehension of a particular concept through the use of pre-tests and post-tests or a comparison group. The idea is that once you have a framework established, a variety of measurement approaches and methodologies are available, but the framework must come first.

Each of the cases above contributes some advice for planning.

- Capture and analyze learning in the context in which it occurs.

- Assess the usability of the technology and how it affects students' personal learning experience.

- Look beyond measurable cognitive gains into changes in the learning process and practice.

- Consider organizational issues in the adoption of mobile learning practice and its integration with existing practices.

- Span the lifecycle of the mobile learning innovation that is evaluated, from conception to full deployment and beyond.

And finally, when working with emerging technologies, it is important to remember to evolve our studies and frameworks as the technology evolves. These approaches should not be static, but should change as the adoption of the technology and corresponding pedagogies mature. Constructing our research so we are informing future phases is always important, but is especially important when working with an emergent technology.

References

Born, C., & Nixon, A. L. (2012, March). Closing in on vocabulary acquisition: Testing the use of iPods and flashcard software to eliminate performance gaps. SEI Case Study. Washington DC: EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/library/resources/closing-vocabulary-acquisition-testing-use-ipods-and-flashcard-software-eliminate-performance-gaps

Naismith, L., Sharples, M., & Ting, J. (2005, October). Evaluation of CAERUS: A context aware mobile guide. Presented at mLearn 2005, Cape Town, South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.mlearn.org.za/CD/papers/Naismith.pdf

Nestel, D., Ng, A., Gray, K., Hill, R., Villanueva, E., Kotsanas, G., . . . Browne, C. (2010). Evaluation of mobile learning: Students' experiences in a new rural-based medical school, BMC Medical Education, 10(57). doi:10.1186/1472-6920-10-57

Traxler, J., & Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2005). Evaluating mobile learning: Reflections on current practice. Retrieved from http://www.mlearn.org.za/CD/papers/Traxler.pdf

Vavoula, G. N., & Sharples, M. (2008). Challenges in evaluating mobile learning. Presented at mLearn 2008, Ironbridge Gorge, Shropshire, UK. Retrieved from http://www.mlearn.org/mlearn2008/

Wang, M., Novak, D., & Shen, R. (2008). Assessing the effectiveness of mobile learning in large hybrid/blended classrooms. In J. Fong, R. Kwan, & F. L. Wang (Eds.), Hybrid Learning and Education (pp. 304-315). Retrieved from http://www.docstoc.com/docs/38964563/Assessing-the-Effectiveness-of-Mobile-Learning-in-Large-HybridBlended

Veronica Diaz, Ph.D., is the associate director of the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative, EDUCAUSE.

Opinions expressed in Innovation Showcase are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the League for Innovation in the Community College.