Barriers to Academic Success: A Qualitative Study of African American and Latino Male Students

Students of color, males in particular, face significant challenges in higher education. African American male students, on average, are less successful than other racial/ethnic groups, including African American women. Compared to Asian/Pacific Islander or White/Non-Hispanic students, they are less likely to succeed in both developmental and college-level coursework and are more likely to drop out. Latino students are the least likely of all racial/ethnic groups to transfer. African American students and Latino males have the lowest persistence rates (Elgin Community College, 2010).

Students of color throughout the country are significantly less likely to persist than other racial/ethnic groups (Adelman, 2005), and African American males in particular lag behind on almost every indicator of academic achievement (Esters & Mosby, 2007). Reasons for these trends are numerous and stem from inequalities in race and class, and in chronic unemployment to a lack of role models and advocates for men of color (Gavins, 2009). In this research report, the most common barriers facing these two groups of minority male college students will be explored.

Methodology

Eight focus groups were organized to obtain further information about African American and Latino males. A total of 40 male students responded to the invitations and participated. They were asked to name barriers to success they experienced in general and at college, and to offer recommendations for future action.

Main Shared Themes

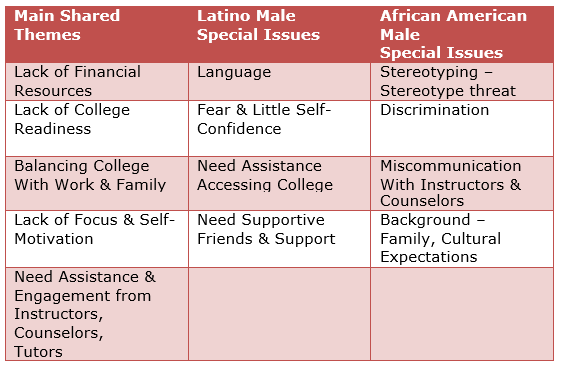

Table 1 displays the main themes that emerged from these conversations for both African American and Latino males, for African American males only, and for Latino males only.

Table 1

Financial Aid and Paying for College

Across all groups, financial resources and paying for college emerged as a significant barrier. One Latino male, who completed two consecutive semesters, noted that his peers are not educated during high school about college and financial aid. He reported, “They don’t even think about going to community college.” Building on this sentiment, another Latino male stated that it is very difficult, almost futile, to get scholarships: “What’s the point? It is hard to find jobs using a degree.”

Even when financial aid is made available, respondents reported that barriers surface in other ways—from a misunderstanding of how to use aid funds to confounding barriers related to aid awards. An African American student in this sample relayed an incident about a peer being confronted by a tutor, claiming he was wasting money by not coming to class. The student responded, “It’s not my money.” The man retelling this incident admitted that some of his classmates just want to get aid for personal use. Others noted that federal programs create further obstacles; one respondent said government programs force students to take on more credits than students can handle to meet eligibility requirements for housing rates and insurance. These comments suggest that issues related to accessing financial aid and understanding the value of financing an education are complex and warrant careful examination.

College Readiness

The next major barrier to emerge was college readiness. This theme emerged through a variety of related terms, including unprepared for placement tests, poor computer skills, poor writing skills, poor time management, unfamiliar with technology, no access to computers at home, don’t know what to study, test anxiety, fear of the unknown, general anxiety, and classmates not prepared with the basics. Students from both groups reported receiving little or no support or guidance from their families.

One African American student who completed at least two consecutive semesters confessed that he had never been a good student, stating: “I had to realize the power of studying.” He talked about poor study habits, poor math skills, a failure to consider the future, and just enjoying life and living in the moment. He shared that he has identified with his son having problems in school and described how he has become proactive in encouraging his son to study and complete his homework.

Balancing College With Work and Family

The third main issue for both populations is balancing college with work and family life. Barriers in this category included time management, goal setting, making priorities, unmotivated to attend class, lack of interest in class, and childcare responsibilities at home. Many students stated that they are the first generation in their families to attend college and that they “have no role models,” a finding recently highlighted in a College Board report (2010). A few times it was mentioned that if the parents do not have a college education, they do not encourage or expect their children to pursue a college credential.

Even among students who were expected to “make something of yourself,” many did not receive much guidance about college. Rather, they were expected to get a job. Related to this category were tensions from friends and other social circles. Students reported barriers of peer pressure and “hanging out with the wrong crowd—not everyone goes to college.”

Lack of Focus and Self-Motivation

With no assistance or little knowledge of the educational system, it is perhaps not surprising that members of both groups named lack of self-motivation as another major barrier. Statements in this category included: lack of initiative to get education, not focused/mentality, lack of passion for attending college or investing in an education, and parents made [them] attend.

Some students, having completed two or more consecutive semesters, shared wisdom from their successful journey with others, for example:

As I get older, I realize the value of education; maturity sets in. I think what’s in it for me right now and I think about how my parents never went to college and they have hard jobs making little money. My dad is working two jobs. Without college, this is how it’s going to be. I want to be something else in life; I want to show my parents that they came to this country to make life better for me and they have succeeded. I want to enjoy learning, going to school, as I now understand the impact it has on my life. I enjoy the process as well as the product. (paraphrased)

Lack of Assistance and Engagement

The final theme that emerged was a lack of engagement between some students and instructors, counselors, and tutors. Participants stated that they need more quality teacher contact. “[The] teachers don’t care,” stated one African American male. A Latino male suggested “more flexible office hours.”

Several students offered their own examples of “bad teaching.” It was reported that one instructor did not teach, but just put the information on the board; another did not return a call from a student dealing with an urgent personal injury. In relation to classroom instruction and the learning process, another barrier named was “getting bored doing the same thing over and over again.” An African American student remarked that teachers should be required to have a “high pass rate.”

On a positive note, in one uncommon example, an instructor actually saved a student’s college career by personally purchasing a voice recognition program that the Disabilities Office presumably did not have. These barriers and comments raise questions about the institutional communication culture, teaching effectiveness, style, and approach, as well as students’ expectations and participation.

Special Issues by Group

In addition to common challenges, African American and Latino males identified unique combinations of challenges and barriers

Special Issues for African American Males

The majority of African American students participating in the focus groups reported barriers related to stereotyping and discrimination. Most of their examples referred to encounters with professionals at this college: instructors, counselors, and tutors. More than once, their perceptions of being belittled, treated as ignorant, and being addressed with no expectation of success were identified as major barriers.

In one focus group, an African American student described an incident in which African American students were singled out: “We are being singled out as Black. Others don’t have the same issues. The white girl in class clinches her purse. They don’t ask a question until you prove you are not ignorant.” Stereotyping oversimplifies and reduces the uniqueness of human beings, labeling students, for example, according to culture or race; they are then viewed as belonging to one particular group and behaving according to alleged group norms. During one incident on campus, an African American male was asked to solve the issue for “all African Americans,” with an underlying assumption that all African American people on campus know each other. Another student elaborated on his perspective: “There are certain rules just for African American students.” Stereotyping on campus can extend to family and culture, where a sharp dichotomy can exist between the students’ own hopes and family/cultural expectations for success. Stereotypes like “African American or Black men don’t go to college” and “school is not the best place for a Black man” were mentioned more than once.

Many student comments suggest that the culture of college can be at odds with the culture outside academia to which they are expected to conform. The theme is also commonly reported among first-generation college students (Engle, Bermeo, & O’Brien, 2006). Given these experiences, it is no surprise that another stereotype was identified as African American men being “antisocial” and “not speaking up.” Indeed, student responses indicate that at least some African American male students experience stereotype threat—their performance and academic success is being influenced negatively by stereotypes communicated by authority figures.

More than one African American male in this sample commented on the miscommunication between students and faculty. Often it was difficult to discern whether the miscommunication was also related to stereotyping. As one African American male relayed, “When you raise your hand they look surprised—think you are cracking a joke.” Several perceived that faculty misconstrue intentions, assume something else, and render students “embarrassed to ask questions.” One student described his experience exemplifying both possible miscommunication and stereotyping: “Teachers do not expect success, because you are the black guy, you are here for sports. A teacher will not call on me. They assume I’m going to drop out halfway in the semester. I am asked: ‘You’re sure you want to be here?’”

Finally, it is important to note that African American male students who had been successful for at least two consecutive semesters also shared their own strategies for success, for example:

Set a goal that you are going to do it and make up your mind to listen. Take advantage of those things available to you such as tutoring, etc., and work on problems at home. Go talk to your instructors and take advantage of classroom time, study time, and tutoring time, to make sure you understand the information. Take time to read the textbooks and read ahead. It might be hard, but it’s about not giving up and overcoming any issues you might have. Invest time into your studies to do well and always ask others for help if you don’t understand something.

Special Issues for Latino Males

Though according to the quantitative data, Latino males were more successful than African American males, qualitative data suggest that they struggle as a distinctive population with unique challenges related to language and access to college. In fact, language was named as the major barrier to their success in higher education. One student stated that ESL (English as a Second Language) is offered only in certain areas. The need for bilingual materials and Spanish books, as well as tutors, teachers, advisors, and counselors who are equipped to work with them and have flexible hours, were emphasized.

Students also expressed a fear of rejection, fear of success, and a lack of self-confidence. Some felt “comfortable with where they are” (outside of college), begging the question of why anyone would want to plunge into the unknown (go to college). The need for social support, clubs, friends, a connection, and social network was expressed. Some of these students also stated that they have children, and thus have the added obligation of supporting a family as well as attending college. Time management for these students includes balancing work, family, childcare, and college, and “going to school [is] not #1.” Some are afirst-generation college students and have no role models for how others manage this mix.

Another major barrier for this group was accessing college or knowing the steps to college. “We don’t receive much guidance growing up” and “We aren’t educated about the opportunities” were comments that came up. Student comments emphasize the lack of family and cultural support; many students are the first generation in their families to attempt a college career. Latino male students need more support and guidance in accessing college and navigating their way through course selection, course registration, and so on. For instance, one Latino male submitted,

We need help transitioning from high school, coordinating school with work schedules, making future plans, improving poor study habits and math skills. We need assistance in navigating college and coaching to improve personal skills: We need to learn to establish priorities, set limits, be responsible, get classes organized, schedule classes with time in between for study. We need assistance to fill out forms for financial aid and scholarships, to find work that has reimbursement programs.

Discussion and Implications

Why do these barriers continue to exist? Although there is much literature on the reasons for these achievement gaps, very few studies offer concrete strategies or research-based interventions for addressing these problems. One study in 2007 documented Hispanics/Latinos as the second largest group in U.S. schools, yet they are still considered a minority group and have one of the lowest academic success rates (Kohler & Lazarin, 2007).

According to the literature, Latino students face obstacles in terms of language proficiency, social and cultural capital, and unofficial college access information, as well as a college-going identity as a social group (Collatos, Morrell, Nuno, & Lara, 2004). Researchers have compared educational backgrounds of different populations and found that Latino students are much less likely than White students to have a parent with an earned educational credential and to be well prepared for collegiate-level work (Swail, Cabrera, Lee, & Williams, 2005). In addition, they are much less likely to aspire to earn a postsecondary degree, to enroll in a postsecondary institution, and to have earned such a degree by 26 years of age (Swail et al., 2005).

A study from 2009 (Marsico & Getch) emphasized that specific programs are needed to support the success of Latino students and to narrow the achievement gap. The focus was on the act of applying to college, which appeared to be particularly difficult for this population. Given the comments shared by male Latino students, and the subsequent data collected through the focus groups, this is of particular significance. These investigators found that the implementation of collaborative systemic interventions targeting senior students and their families at a suburban high school made a notable impact on the number of seniors enrolling in college that school year. As they concluded, it is important that professionals are aware of this achievement gap and the fact that both students and their families need advocates to assist them in navigating the “postsecondary maze” (Marsico & Getch, 2009).

According to research on African American male students, barriers and achievement gaps in higher education are due to a complex set of factors ranging from societal racist practices to local budgetary cuts in programs and psychological phenomena associated with being a member of this particular social group. Inequalities in race and class, lack of role models and advocates, communities with chronic unemployment, and high levels of residential segregation all play a role (Gavins, 2009).

Additionally, research indicates that the expectations teachers and counselors have of students play an integral role in the development and maintenance of students’ college aspirations. Moreover, the lack of postsecondary motivation and aspiration, lack of academic achievement, and three socioeconomic factors—finances, parental education, and family influence—present common barriers impeding success for African American males in higher education (Griffin, Jayakumar, Jones, & Allen, 2009). There is much evidence that educational policymaking has neither increased access nor ensured equity for African American students in higher education, according to a 2009study (Harper, Patton, & Wooden, 2009). Referring to CRT—Critical Race Theory—as an analytical framework, researchers studied policies affecting African American students that produce and maintain racial disparity. They proposed that institutional policies be analyzed and further developed to address the two main issues threatening African American students: access and equity.

Studies on stereotype priming and stereotype threat point to situational factors contributing to individuals being affected by specific stereotypes (Marx & Stapel, 2006). The student responses in this study suggest that at least some African American students are experiencing both stereotype priming and stereotype threat (as stated above). Addressing this issue would be one step to benefit both of these distinct populations, as well as other students experiencing similar phenomena (Rydell, McConnell, & Beilock, 2009).

Conclusion

In summary, the barriers and challenges identified by these male students are in alignment with current research, and overlap some barriers mentioned by other student populations. The long narratives and concise statements provided by respondents attest to the fact that students possess much self-awareness and truly ask that their voices be heard. Students suggested steps for overcoming barriers and called for better relationships and communication with professors, instructors, counselors, tutors, and other personnel. They seek further assistance with organizational and administrative procedures, as well as encouragement, support, and coaching inside and outside of the classroom.

Questions still remain concerning the patterns of success for larger groups of students. Given the size of this sample, one main recommendation is to collect further qualitative data from both male and female students of diverse social groups via focus groups, personal interviews, and narrative essays. In terms of data-driven strategy development, the greatest challenge lies in leveraging the strengths of all to lift as many barriers as possible.

References

Adelman, C. (2005). Moving into town – and moving on. The community college in the lives of traditional-age students. Washington DC; U.S. Department of Education.

Collatos, A., Morrell, E., Nuno, A.. & Lara, R. (2004). Critical Sociology in K-16 early intervention: Remaking Latino pathways to higher education. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 3(2), 164-179.

Elgin Community College. (2010). Achieving the Dream [Data file].

Engle, J., Bermeo, A., & O’Brien, C. (2006). Straight from the source: What works for first-generation college students. Washington, DC: Pell Institute.

Esters, L. I., & Mosby, D. (2007), Disappearing acts: The vanishing Black male on community college campuses. Diverse Issues in Higher Education, August 23.

Gavins, R. (2009). A historical view of the barriers faced by Black American males in pursuit of higher education. Diversity in Higher Education, 6, 13-29.

Griffin, K. A., Jayakumar, U. M., Jones, M. M., & Allen, W. R. (2009). Overcoming barriers: Characteristics of Black male freshmen between 1971 and 2004. Diversity in Higher Education, 6, 155-179.

Harper, S., Patton, L., & Wooden, O. (2009). Access and equity for African American students in higher education: A critical race historical analysis of policy efforts.” Journal of Higher Education, 80(4), 389-414.

Kohler, A. D., & Lazarin, M. (2007). Hispanic education in the Unites States. Statistical Brief No. 8. Washington DC: National Council of La Raza.

Marsico, M., & Getch, Y. (2009). Transitioning Hispanic seniors from high school to college. Professional School Counseling, 12(6), 458-462. Retrieved from Academic Search Premier database.

Marx, D., & Stapel, D. (2006). Distinguishing stereotype threat from priming effects; On the role of the social self and threat-based concerns. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(2), 243-254.

Rydell, B. J., McConnell, A. R., & Beilock, S. L. (2009). Multiple social identities and stereotype threat: Imbalance, accessibility, and working memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 949-966.

Swail, W. S., Cabrera, A. F., Lee, C., & Williams, A. (2005). From middle school to the workforce: Latino students & the educational pipeline. Washington, DC: The Educational Policy Institute.

The College Board. (2010). The educational crisis facing young men of color. New York, NY: Author.

Nina L. Dulabaum is a psychology and sociology professor at Sauk Valley Community College in Dixon, Illinois.

Opinions expressed in Innovation Showcase are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the League for Innovation in the Community College.