Centers for Inclusive Democracy: An Integrated Approach to Fundamental Values for Higher Education

The Maricopa County Community College District (MCCCD) enrolls nearly 140,000 students annually at 10 independently accredited colleges and 31 satellite locations. MCCCD is the top provider of undergraduate education to students of color in the state of Arizona, and 48 percent of its students are first-generation college matriculants (Maricopa Community Colleges, 2024). The district offers degrees and certificates across more than 600 programs, including new bachelor’s degrees in certain fields.

MCCCD, like every institution of higher education, has been buffeted by political, social, epidemiological, and economic headwinds challenging values fundamental to the mission of higher education generally, and especially to the mission of community colleges (Boggs, 2010). At MCCCD, these challenges have come not only from the external environment, but also from various constituent and affinity groups within the district. Each group tended to view issues facing the institution through the particular lens with which they were most comfortable, whether that be inclusion, free expression, academic freedom, or civic engagement. MCCCD believed that in order to successfully address its external challenges, it first had to engage in a reexamination of and recommitment to its institutional values. Through an internal assessment process, we learned that while values and lenses may sometimes appear to conflict, they are best understood and implemented through an integrated approach that recognizes overlapping similarities and draws on individual strengths.

At the direction of the Chancellor, co-chairs convened a taskforce with broad representation to begin the internal assessment in spring 2021. During the spring and summer, the taskforce met several times to talk through the differing perspectives present; to discuss relevant underlying theoretical foundations; and to learn some of the applicable history, philosophy, and law. From these discussions, many useful and productive understandings were achieved that allowed the work to continue in a consensus-driven manner. Among the byproducts of the meetings was an agreement that the approach would be systemwide, based on MCCCD as an educational institution and not as a conduit for realizing personal moral or political commitments. Central to this approach was, surprisingly enough, a more thorough realization of the applicability of the history of pirate democracy (Chartier, 2010). The history of pirates self-organizing, selecting their leaders, and equitably distributing treasure informed the group’s understanding of pluralism, inclusion, and other democratic values.

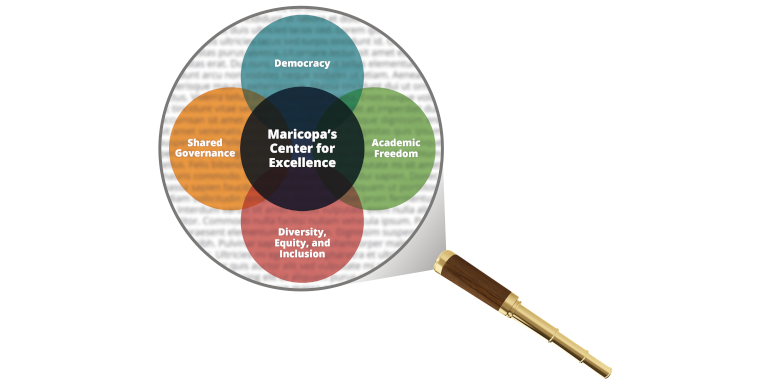

By that summer, the taskforce had developed a proposal for an integrated framework using the imagery of overlapping lenses (refer to top image). Like a spyglass, no lens operating on its own would be sufficient to provide a complete enough perspective to navigate the treacherous waters. This framework, itself the product of an inclusive, consensus-driven process, was then presented by members of the taskforce to various constituencies and governance groups throughout MCCCD to promote the approach, receive feedback, and adjust the model as needed.

As part of its organizing meetings, participants in the taskforce developed this word cloud.

The Center for Excellence in Inclusive Democracy was born shortly thereafter. It began its work to ensure that institutional decision-making took into account the overlapping perspectives of its four lenses operationalized as follows:

- Democracy. The taskforce construed democracy broadly to include various norms about equality, rights, freedom, compromise, free speech, tolerance, and civility, among others. It acknowledged that higher education prepares students for lives as engaged democratic citizens and participants in our economic system.

- Shared Governance. The taskforce emphasized striking a balance between inclusion—in the capacious sense of including all perspectives and identities—and the value of expertise and authority in arriving at wise decisions. It was also determined to ensure that classified staff had sufficient voice about intramural concerns despite their diminished First Amendment free speech rights as public employees as determined by Garcetti v Ceballos.[i] It further recognized that faculty sometimes had different levels of participation and influence in shared governance that were structural in nature, based on their institutional roles.

- Academic Freedom. The taskforce acknowledged that academic freedom is at the heart of our educational mission and, properly understood, is essential in “promoting rational discourse, academic inquiry, and honest pedagogy” (Villanueva-Saucedo & Coughlin, 2021, p. 6). The taskforce accepted the understanding of academic freedom endorsed by MCCCD’s Committee on Academic Freedom and promulgated by Professors Matthew W. Finkin and Robert C. Post (2009) in For the Common Good: Principles of American Academic Freedom.

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI). The taskforce agreed that MCCCD’s culture would “seek . . . to ensure that every college community member is valued, welcomed, and supported, without exception,” and value all perspectives of students and employees because “diversity enriches the educational experience, providing us with opportunities to learn from one another and the variety of perspectives, experiences, and beliefs, even when different from our own” (Villanueva-Saucedo & Coughlin, 2021, p. 7). The taskforce further committed to “fairness, impartiality and the equality opportunity for all to fully participate in the educational experience and find success” (Villanueva-Saucedo & Coughlin, 2021, p. 7). Through civil dialogue, respectful listening, and with an active commitment to minimizing or removing barriers, students and employees will be more likely to experience a sense of belonging and inclusion.

With this integrated framework in place, MCCCD set out to address various internal tensions that were impeding institutional decision-making and/or action. The authors were involved with three projects that effectively deployed the new framework. The projects included issuing recommendations regarding DEI-related questions in the system hiring process; issuing recommendations about accessibility standards for meetings, convenings, and communications for staff and faculty; and developing guidelines to assist MCCCD leaders regarding the issuance of public statements.

While the specific outcomes were positive and fruitful, the details of each project are beyond the scope of this article. Of greater note is that progress in each of the three areas was previously stymied by unresolved internal, values-based tension that appeared to be intractable before the spyglass approach was developed and implemented. Each project related to multiple lenses, and the dialogue of participants engaged in the work was civil and respectful (though occasionally tense), ultimately resulting in consensus in all cases. The value of consensus on contentious issues cannot be understated, as support for decisions such as these is essential in ensuring their successful implementation.

One could imagine other areas corresponding to the four lenses where such an integrated, holistic approach would be valuable. Civic engagement work, for instance, is commonly siloed either in a faculty service learning paradigm or in a student activities office. Bringing multiple lenses, such as democracy and DEI, to bear could result in a more integrated and robust civic engagement program that could result in greater capacity-building for colleges and systems to do this work. Policies on invited speakers could also benefit from such an integrated approach, incorporating academic freedom, democracy, and DEI in meaningful and mutually beneficial ways to develop a policy that respects the various values at play. Acknowledging the national dialogue around DEI and related legislation and reframing the conversation by emphasizing inclusion in terms of democracy illustrates the value of a multi-lens approach, as does the intentional naming of the Center for Excellence in Inclusive Democracy.

As the center continues to grow and evolve, we plan to begin a fellows program for staff and faculty who wish to engage more deeply with this work and who can serve as project leaders and subject matter experts. Tapping into expertise across the system will allow for continued growth of the center and its work without necessitating additional full-time staff positions. This approach acknowledges the economic realities facing community colleges generally, and MCCCD specifically, while still expanding the much-needed work of the center.

Another strategy for expanding upon the center’s work has the been the creation of cross-functional advisory teams, including a Committee on Freedom of Expression and a Civics Council. Bringing together representatives from across the 10-college system brings multiple, diverse voices into critical conversations about MCCCD’s core values. This also helps the system create shared meaning around the language of these values, increased alignment to a systems approach, and organizational capacity.

An important philosophy of the center is to build organizational capacity to engage in the work through a multi-lens approach rather than a centralized, hierarchical model. A system as large and complex as MCCCD poses challenges in creating a cohesive approach and philosophy. Rather than the center being viewed as a siloed initiative at the system level or a sideline project, building capacity and expertise across the district ensures an institutionalized framework. Thus, MCCCD is better situated to navigate not only the current storm, but also the long-term weather patterns that confront higher education.

References

Boggs, G. R. (2010). Democracy’s college: The evolution of the community college in America. Community College Journal, 82(4).

Chartier, G. (2010). Pirate constitutions and workplace democracy. Jahrbuch Für Recht Und Ethik/Annual Review of Law and Ethics, 18, 449-467.

Finkin, M. W., & Post, R. C. (2009). For the common good: Principles of American academic freedom. Yale University Press.

Maricopa Community Colleges. (2024). Fast facts. https://www.maricopa.edu/about/institutional-data/fast-facts

Villanueva-Saucedo, D., & Coughlin, J. (2021, September). Center for Excellence Taskforce initial recommendations [Unpublished internal report]. Maricopa County Community College District.

Deanna Villanueva-Saucedo, M.P.A., is Associate Vice Chancellor, Center for Excellence in Inclusive Democracy, and Eddie Genna, J.D., Ph.D., is Strategic Advisor to the Chancellor at Maricopa County Community College District in Tempe, Arizona.

Opinions expressed in Leadership Abstracts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the League for Innovation in the Community College.